13 April 2007

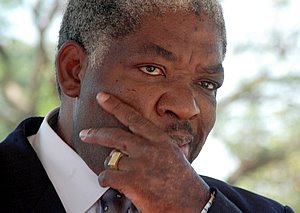

Mondli Makhanya (Sunday Times Editor)

There's this old saying about how the one thing we learn from history is how we learn nothing from history. It always comes back to me when I think of the events of Good Friday, 2000. Dozens of us journos had gathered at the Elephant Hills Hotel in Victoria Falls to cover a make-or-break summit that would stop Zimbabwe's slide into the abyss. The government-backed land invasions were in full force; opposition members campaigning ahead of that year's June parliamentary elections were being beaten and tortured by police and Zanu PF militias; the media and the judiciary were being strangled; the Zimbabwean dollar was heading south in a most dramatic fashion; fuel shortages were rife and the general economy was in free fall. So South Africa's President Thabo Mbeki, Mozambique's Joachim Chissano and Namibia's Sam Nujoma descended on Victoria Falls with a view of talking nicely to Zimbabwe's President Robert Mugabe .

They came out of the marathon meeting brimming with optimism. They told us that Mugabe had agreed to a series of measures to restore normality to a country that had been one of post-colonial Africa's shining stars. Among the measures were that war veterans would be removed from the farms within 30 days; the rule of law would be restored and conditions for free political activity would be created. On the economic front, an orderly land-reform programme would be agreed on and negotiations on funding it would be entered into with Britain and donor agencies. When queried about why they were so confident that Mugabe would meet his end of the bargain, the three presidents expressed irritation that such a question could even be asked. "He is a head of state making a commitment to fellow heads of state and that is good enough. Why would you want to question his integrity?" was the basic response.

The following week, Mugabe and his lieutenants were traversing the countryside, repudiating everything that had been said at Victoria Falls. The message to the masses: there is no way we will order Zimbabweans off the land they have reclaimed from the colonialists; there is no way we will set comrade against comrade by getting security forces to evict war veterans from occupied farms; there is no way we will allow the stooges of colonialists (the Movement for Democratic Change) to campaign to give the country back to the British. Point by point they rubbished the Good Friday agreement, the very commitment that man of integrity had made to fellow heads of state. I am writing this column on Good Friday 2007 (yes, some of us poor sods had to get up this morning to produce the newspaper you are holding in your hands) a week after the South African Development Community heads of state gathered in Tanzania, where Mugabe's colleagues received a commitment from him on restoring political stability to his country.

In terms of the Dar es Salaam minute, Mugabe agreed to a process to enter into dialogue with his rivals and other sections of Zimbabwean society. By all accounts, the SADC leaders were quite tough on Mugabe behind closed doors. And they walked away believing that the man of integrity would help them to help himself. But a day after the summit, Mugabe was back on the podiums, proclaiming that his brother leaders had in fact backed his errant ways because they believed his version that the imperialists were behind the opposition. Over the same weekend, his goons beat up more opposition leaders and jailed more activists. And Mugabe was endorsed as a candidate for yet another term of office - all as if nothing had happened in Dar es Salaam. The point is that if South Africa and its neighbours had been willing to learn from history, they would have known by now that Mugabe is a liar who has no respect for them or the offices they occupy.

A question that is asked of those who are critical of the so-called quiet diplomacy approach is: "What were we expected to do?" The answer should always start with what they should not have done. They should not have legitimised him by endorsing three stolen elections and by repeatedly denying — in the face of incontrovertible evidence — that there was erosion of human rights and democratic practice. At various international forums our representatives should not have acted as Mugabe's bodyguards. Here at home the government and the ANC should not have given Zanu PF revolutionary credentials when it was clear there was nothing left in the party that said "liberation movement". So what could we have done and what can we still do?

The first step for the South African government is to treat Robert Mugabe with a great degree of distrust. The next step would be to get the rest of Zimbabwean society, mainly the civil society activists who we have betrayed, to trust our honest-broker bona fides. And then we need to speak loudly about the principles of the African Union charter and the SADC treaty and protocols - documents that the Mugabe government has endorsed. These are not imperialists' impositions, but minimum standards that we on the continent have agreed to. They are a legitimate platform for intervention.- The Sunday Times.

Yahoo! Answers - Got a question? Someone out there knows the answer. Try it now.

No comments:

Post a Comment