Zimbabwe Crumbles

Brutal Honesty

By Jeff Purcell

Apr 9 2007

Apr 9 2007

The crisis in Zimbabwe might be reaching its climax. Dozens of stories have appeared in the most prominent publications describing the freefall in the country. If only our eyes were wider sooner.

Zimbabwe's 13 million people have the lowest life expectancy on earth — women can expect death at 34 and men by 37. Inflation is over 1000 percent and for some time currency has been used as toilet paper in many places, including the capital, Harare. Because trade stopped and shelves were empty, the money retained but one use. In May, a roll of toilet paper cost over 140,000 Zim dollars.

In July I was in Durban, South Africa, and I met people from Zimbabwe. Some were refugees, selling tomatoes and wooden souvenirs on the side of the road. Malcolm had come from Zim the prior year, and worked near my apartment. Every week or so, on my walk to work, we talked for a few minutes. When news surfaced that the country's President, Robert Mugabe, had recently completed a new 26-bedroom palace — while the rest of his country was starving — Malcolm said, "We suffer for his riches." Tom, another Zim man I met, gave me a 100,000 Zimbabwean dollar note. It had an expiration date printed six months from then — a signal of the currency's near-collapse.

Mugabe has done much to destroy local health clinics and to ban media into his country. The BBC is barred, for instance, and most reports we get from Zim are filed from Johannesburg, 600 miles away. We already viewed Zimbabwe from a distance, but for the past six years our field of vision shrank further. Credible estimates, however, indicate that about 33 percent of the population carries HIV. Without a health infrastructure (nurses, clinics, doctors, pharmacies) and funding for adequate care, the virus rapidly becomes AIDS, and soon infections and ailments that can be cured inexpensively elsewhere kill Zimbabweans early.

Last May, Zim's National Pharmaceutical Company ran out of money. The anti-retroviral drugs that keep HIV from multiplying were administered to about 20,000 people in the country, out of an infected total of around 1/3 of the adult population, so roughly 3 million people. Zimbabwe is ravaged by HIV: more than one in 10 newborns are expected to die of an AIDS-related illness by five and 25 percent of the labor market will die by 2025. There are more orphans per capita there than anywhere else in the world. The amount of money needed to buy the next batch of drugs was $7.4 million American dollars, and the company only had $106,000.

Consequently, the few patients receiving the medicines stopped treatment. As a result, they cannot take ARVs again because their HIV will become resistant. As the virus replicates, it will prevent them from resisting minor infections and routine viruses. These people go from statistic to statistic. And all the time they're just data points.

Today, all this adds up, quickly, to millions of people dying early and painfully. Zimbabwe didn't collapse overnight; on the sidelines we've watched its people decline for decades. Three decades ago, Mugabe led the Zimbabwe African National Union to victory over what remained of colonial Rhodesia. Cecil Rhodes' British South Africa Company drove out everyone who lived there and divided the assets of land, minerals and people. The settlers were particularly opposed to ending their racist control over the land and government — after decades of settler rule, they declared independence from Britain in 1965, basing the declaration on America's. The world took notice and put sanctions on Ian Smith's Rhodesia, but mostly the history played out without much interest from abroad after that.

It wasn't until almost 1980 that the war between black African revolutionaries and white settlers finally ended. The Rhodesians conscripted every white man to fight in the most brutal ways — anthrax was spread on food stocks, and cholera and rat poison were dumped in rivers. When it all ended, Mugabe became president, and it was time to rebuild. But in terms of land reform, there was no success. The government could return land, but only if the whites who owned most of it agreed to sell, the "willing buyer-willing seller" model. Their refusal meant that most Zimbabweans stayed poor and landless. Though the farms were productive and Zimbabwe could feed itself, the black majority population never touched a profit, and continued to live as they had before their country became independent. As the population grew after independence and productive requirements on the soil increased, more and more citizens demanded land reform. Mugabe's rule was challenged, and he silenced and killed thousands of opponents, yet kept winning reelection. Though recent elections were clear frauds, his supporters are still many. One group of opponents, the Movement for Democratic Change, has spearheaded a campaign for free and fair elections, a return to media and political freedom and an end to the policies that have starved their country. In the past year, Mugabe has become increasingly violent against urban supporters of the MDC, and has razed thousands of shack settlements, like the one Malcolm grew up in.

He's blamed the British and Americans for supporting his rivals, but he's wrong. The British stopped funding land reform when Mugabe started stealing farms for his cronies. And the U.S. has barely made a sound. South Africa, too, has been silent, unwilling to disturb Mugabe for the sake of the millions he makes "suffer for his riches."

Zimbabwe is a complicated country with a deep history. It is exceptional in so many ways. But so often we imagine countries like Zimbabwe to be only a place of hungry victims. In America, we're used to treating Africa as one large village, or one tiny nuisance. But neither of those things is true. Africa is huge, heterogeneous and complex. There are some who are simply good and bad, and rich and poor, but there are millions more who are driven by many factors, and not simply any one thing.

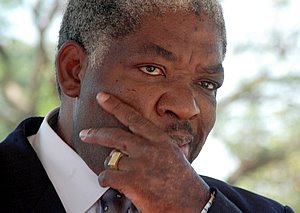

A snapshot of Zimbabwe is an attempt to complicate its situation, not reduce it to a children's story. As Mugabe's rule comes toward its end, the MDC's Morgan Tsvangirai is recovering from brutal attacks. Last month Mugabe's police nearly beat him to death. But he fights to regain his strength, and not become another number. He fights, and the next day comes nearer to his 56th birthday. Zim is worth our efforts and our interest, and not just when it freefalls. It's not a world away from us — there's one world for us all.

Jeff Purcell is a graduate student in Africana Studies. He can be reached at jlp56@cornell.edu. Brutal Honesty appears Mondays.

Zimbabwe's 13 million people have the lowest life expectancy on earth — women can expect death at 34 and men by 37. Inflation is over 1000 percent and for some time currency has been used as toilet paper in many places, including the capital, Harare. Because trade stopped and shelves were empty, the money retained but one use. In May, a roll of toilet paper cost over 140,000 Zim dollars.

In July I was in Durban, South Africa, and I met people from Zimbabwe. Some were refugees, selling tomatoes and wooden souvenirs on the side of the road. Malcolm had come from Zim the prior year, and worked near my apartment. Every week or so, on my walk to work, we talked for a few minutes. When news surfaced that the country's President, Robert Mugabe, had recently completed a new 26-bedroom palace — while the rest of his country was starving — Malcolm said, "We suffer for his riches." Tom, another Zim man I met, gave me a 100,000 Zimbabwean dollar note. It had an expiration date printed six months from then — a signal of the currency's near-collapse.

Mugabe has done much to destroy local health clinics and to ban media into his country. The BBC is barred, for instance, and most reports we get from Zim are filed from Johannesburg, 600 miles away. We already viewed Zimbabwe from a distance, but for the past six years our field of vision shrank further. Credible estimates, however, indicate that about 33 percent of the population carries HIV. Without a health infrastructure (nurses, clinics, doctors, pharmacies) and funding for adequate care, the virus rapidly becomes AIDS, and soon infections and ailments that can be cured inexpensively elsewhere kill Zimbabweans early.

Last May, Zim's National Pharmaceutical Company ran out of money. The anti-retroviral drugs that keep HIV from multiplying were administered to about 20,000 people in the country, out of an infected total of around 1/3 of the adult population, so roughly 3 million people. Zimbabwe is ravaged by HIV: more than one in 10 newborns are expected to die of an AIDS-related illness by five and 25 percent of the labor market will die by 2025. There are more orphans per capita there than anywhere else in the world. The amount of money needed to buy the next batch of drugs was $7.4 million American dollars, and the company only had $106,000.

Consequently, the few patients receiving the medicines stopped treatment. As a result, they cannot take ARVs again because their HIV will become resistant. As the virus replicates, it will prevent them from resisting minor infections and routine viruses. These people go from statistic to statistic. And all the time they're just data points.

Today, all this adds up, quickly, to millions of people dying early and painfully. Zimbabwe didn't collapse overnight; on the sidelines we've watched its people decline for decades. Three decades ago, Mugabe led the Zimbabwe African National Union to victory over what remained of colonial Rhodesia. Cecil Rhodes' British South Africa Company drove out everyone who lived there and divided the assets of land, minerals and people. The settlers were particularly opposed to ending their racist control over the land and government — after decades of settler rule, they declared independence from Britain in 1965, basing the declaration on America's. The world took notice and put sanctions on Ian Smith's Rhodesia, but mostly the history played out without much interest from abroad after that.

It wasn't until almost 1980 that the war between black African revolutionaries and white settlers finally ended. The Rhodesians conscripted every white man to fight in the most brutal ways — anthrax was spread on food stocks, and cholera and rat poison were dumped in rivers. When it all ended, Mugabe became president, and it was time to rebuild. But in terms of land reform, there was no success. The government could return land, but only if the whites who owned most of it agreed to sell, the "willing buyer-willing seller" model. Their refusal meant that most Zimbabweans stayed poor and landless. Though the farms were productive and Zimbabwe could feed itself, the black majority population never touched a profit, and continued to live as they had before their country became independent. As the population grew after independence and productive requirements on the soil increased, more and more citizens demanded land reform. Mugabe's rule was challenged, and he silenced and killed thousands of opponents, yet kept winning reelection. Though recent elections were clear frauds, his supporters are still many. One group of opponents, the Movement for Democratic Change, has spearheaded a campaign for free and fair elections, a return to media and political freedom and an end to the policies that have starved their country. In the past year, Mugabe has become increasingly violent against urban supporters of the MDC, and has razed thousands of shack settlements, like the one Malcolm grew up in.

He's blamed the British and Americans for supporting his rivals, but he's wrong. The British stopped funding land reform when Mugabe started stealing farms for his cronies. And the U.S. has barely made a sound. South Africa, too, has been silent, unwilling to disturb Mugabe for the sake of the millions he makes "suffer for his riches."

Zimbabwe is a complicated country with a deep history. It is exceptional in so many ways. But so often we imagine countries like Zimbabwe to be only a place of hungry victims. In America, we're used to treating Africa as one large village, or one tiny nuisance. But neither of those things is true. Africa is huge, heterogeneous and complex. There are some who are simply good and bad, and rich and poor, but there are millions more who are driven by many factors, and not simply any one thing.

A snapshot of Zimbabwe is an attempt to complicate its situation, not reduce it to a children's story. As Mugabe's rule comes toward its end, the MDC's Morgan Tsvangirai is recovering from brutal attacks. Last month Mugabe's police nearly beat him to death. But he fights to regain his strength, and not become another number. He fights, and the next day comes nearer to his 56th birthday. Zim is worth our efforts and our interest, and not just when it freefalls. It's not a world away from us — there's one world for us all.

Jeff Purcell is a graduate student in Africana Studies. He can be reached at jlp56@cornell.edu. Brutal Honesty appears Mondays.

New Yahoo! Mail is the ultimate force in competitive emailing. Find out more at the Yahoo! Mail Championships. Plus: play games and win prizes.

No comments:

Post a Comment